Sohad Murrar studies how media and norms affect people’s opinions about social groups. Does media representation matter? Can infotainment aimed at reducing misconceptions really work? In this episode, Sohad gives us a glimpse into what the research says, her own experiences consulting with Hollywood creatives, and how conveying social norms can be a potent way of addressing prejudice.

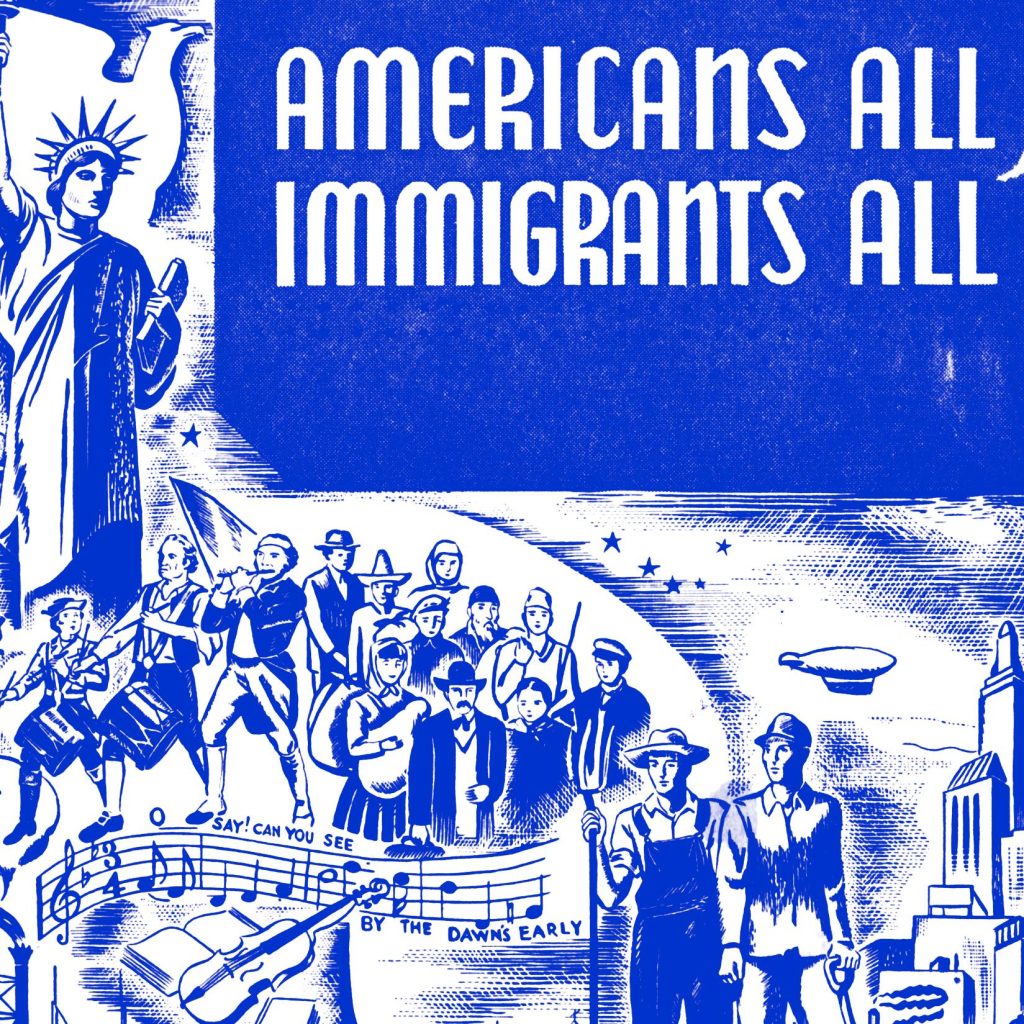

Also at the top of the show, you’ll hear about a radio program from the 1930s: “Americans All–Immigrants All.” You can listen to most episodes of that show at WNYC’s archives. Many of the details about the program and how it responded to anti-immigrant prejudice at the time is thanks to a wonderful book by Susan Herbst: A Troubled Birth: The 1930s and American Public Opinion.

Some of the research Sohad and I talk about includes:

- Thoughtfully produced infotainment can lead to reduced prejudice in viewers (Murrary & Brauer, 2018)

- How stories can foster more positive attitudes toward social groups (Murrar & Brauer, 2019)

- Conveying pro-diversity social norms serves to increase tolerance and inclusion (Murrar, Campbell, & Brauer, 2020)

Transcript

Download a PDF version of this episode’s transcript.

Andy Luttrell:

The American story—or like the story of modern America and its inhabitants—is an immigrant’s story. People coming to this land in waves from all over the world in search of opportunity and a better life. For years after the United States were established, immigrants came with relatively little oversight. But several years after World War I—in 1923—when Calvin Coolidge first addressed the country as its president, he said: “America must be kept American…For this purpose, it is necessary to continue a policy of restricted immigration.” And in 1924, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed act, which severely restricted immigration. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed, throwing the country into turmoil. And as political scientist Susan Herbst writes about this time, “as is often the case with racism, long-held discriminatory attitudes toward immigrants and their children were rekindled as economic hardship brought out the worst in many.”

But during this time of anti-immigrant prejudice and questions about what it means to be a true American, a bold radio program burst through the fog. From November 1938 until May 1939, during the coveted Sunday afternoon timeslot, the CBS network aired a 26-part series called…

Archival Radio:

Americans All, Immigrants All

Andy Luttrell:

According to a printed booklet that you could get by writing to the U.S. Office of Education…

Archival Radio:

Send in your request for the free booklet today.

Andy Luttrell:

…Americans All—Immigrants all was “designed to promote a more appreciative understanding of our growing American culture through the dramatization of the contributions made by the many groups which are a part of it.”

Episodes featured entertaining and informative peeks into the experiences of

Archival Radio:

The irish immigrant. Germans in the United States. The Scandinavians and the Finns. Greeks, Turks, and Syrians. Slavs in the United States. Orientals. The French speaking people and the Netherlanders. Italians in America.

Andy Luttrell:

These episodes feature brief history lessons, short radio dramas where native-born Americans meet immigrants and realize their assumptions were wrong, and examples of immigrants who have accomplished great things.

Also, even though it’s kind of awkwardly shoe-horned in there, the series also features an episode focused on African Americans.

Archival Radio:

Today we bring you the story of one immigrant who did not come of his own free will: the Negro. Brought here as slaves for nearly 200 years, emancipated only 75 years ago, the Negroes were and are a challenge to democracy and an important part of our economic and social development.

Andy Luttrell:

These episodes feature brief history lessons, short radio dramas where native-born Americans meet immigrants and realize their assumptions about them were wrong, and examples of immigrants who have accomplished great things. The series was a concerted effort to counter anti-immigrant attitudes, driven in large part by the efforts of a teacher from New Jersey, Rachel Davis DuBois. She was a passionate social activist, advocating for immigrants and minorities. And in the mid-1930s, she connected with John Studebaker who had been appointed as US commissioner of education and who led the Federal Radio Education committee. Together, they conceived of a radio program that would reach the masses and educate them on the struggles of immigrants in order to increase tolerance.

They first went to NBC who rejected it, fearing it would be “unpopular and offensive” to celebrate immigrants’ contributions to the United States as though they might be even more important than those of White people born here.

And it wasn’t perfectly smooth sailing once CBS signed on either. The producers originally wanted to call the series “Immigrants All,” but that got changed to “Immigrants All—Americans All” to emphasize that this wasn’t just about advocating for immigrants, it was about everybody’s role. But then the title got changed yet again to “Americans All—Immigrants All” because after all, when the title would get abbreviated in radio listings, “Americans All” just has a better ring to it than “Immigrants All”…don’t you think?

But nevertheless, I think it’s pretty remarkable that we had a program like this in the 1930s, complete with live orchestral music, a professional host, and scripts read by actors. All with this progressive goal to address intolerance. And sure, when you listen now, it probably doesn’t pass all the criteria for politically correct progressive advocacy. But to their credit, they had consultants from immigrant rights agencies give feedback on scripts and flag potentially problematic content.

So did Americans All-Immigrants All change public opinion? Well, that’s hard to know. Nobody was really testing the effects, and now more than 80 years later, it’s hard to find a clear record. But we have some indications that it may have made a difference. Remember I mentioned that you could write in to request a booklet based on the program. Well, in 1941 for her master’s thesis, one graduate student pored over 81,000 such requests. And sure, most of them said like “Can I please have this booklet?” but she seemed to find that many Americans were moved by the radio series, some even expressing that they wished everyone in the country would be required to listen to it.

Then again, these may just be the very people who never had strong anti-immigrant attitudes to begin with. So we are left with a question: can infotainment like Americans All—Immigrants All, and the way various media portray people from different social groups…can it really break through and change hearts and minds, perhaps even by conveying that respect and tolerance are the norm?

You’re listening to Opinion Science, the show about our opinions, where they come from, and how they change. I’m Andy Luttrell. And this week I talk to an old friend, Sohad Murrar. She’s currently an assistant professor of psychology at Governors State University, and she studies how media and social norms shape the way we think about our diverse social world. Sohad and I first met years ago at this like summer camp for psychology grad students, and I’ve always appreciated the thoughtfulness and enthusiasm that she brings to thinking about important questions. When we met up, I wanted to get the scoop on what her work has to say about entertainment, norms, and prejudice.

Andy Luttrell:

I think as I mentioned in the email, sort of the theme that I see in your work, it sort of encompasses a handful of what might feel like different lines of work, but together they kind of feel like to me how our environments shape the way that we think about other groups, right? Like our attitudes about groups can shape our environments, those environments include our media environment, our social environment. Is that a fair characterization of what you do? Or what’s the through line that you give people for what you do?

Sohad Murrar:

No, I think that is definitely a fair characterization of what I do. I think that my goal is to understand ways of shaping more positive intergroup relations and reducing the prejudices that exist and using different avenues to actually do that. And so, those avenues tend to focus on these different factors that shape the environments that we function in, and those being kind of the media that we consume, or how we can use or leverage certain types of messages, like social norms messages, to actually drive some of those changes.

So, I think that is a fair characterization.

Andy Luttrell:

But it sounds like it’s just happenstance that the ways that you’ve studied to shape intergroup attitudes are those environmental ones. Is that just happenstance or does that seem like, “Well, no, those are the ways to do it as opposed to me trying to shake a person and say you’re wrong, think a different way.” As opposed to reengineering an environment.

Sohad Murrar:

No, it’s not happenstance at all. It’s much more deliberate in that the way I started to think about this topic of prejudice was very much so shaped by how our environments create prejudices, right? Growing up as a Muslim in a post-9/11 world, you start to understand that people have very particular ideas about who you are, and very particular ideas towards you, and it’s not because they’ve actually interacted with you or they actually know who you are, but they have these ideas and they’re coming from somewhere, and you realize that it’s very much so the environment around us and the climate around us that shapes those ideas and attitudes. And when you ask yourself, “Well, how do those perceptions start to come about, where are those conceptions of me and people who look like me or people from other minority groups, how are those attitudes, how are those behaviors, how are those beliefs shaped?” You realize that the media are oftentimes creating a lot of the environment and a lot of the climate.

And so, it wasn’t happenstance. It’s definitely much more deliberate.

Andy Luttrell:

The thing it makes me think too is the issue is if the approach is to go like, “Okay, I’m gonna directly have a conversation with one person and disprove these stereotypes and blah, blah, blah,” if that environment doesn’t change this person gets plopped right back in that environment, right? If those media narratives don’t change, they get plopped right back. So, you can do all you want to say like, “Look at me, I’m not the cartoon that’s in your head,” but until the environment changes, this person goes, “Well, is that just a one-off thing? Because I’m still getting this message from the world around me that tells a particular story about who these people are and how I should act toward them.”

So, does that resonate in terms of why the environment not only is a powerful shaper of prejudice to begin with, but is a necessary component of social change?

Sohad Murrar:

Definitely is a necessary component of social change and I think that this is not a realization that I alone have had, or any one person has independently. I think a lot of people recognize the power and the strength of media on our attitudes and beliefs, and I think that even if you don’t necessarily recognize the influence that media has, you can recognize that media is very pervasive. It’s very prevalent, right? I was recently reading the most recent Nielsen reports, which puts us at consuming over 13, about 13 and a half hours of media every single day. This is what the average American is consuming. And I think even if you don’t necessarily understand how the influence is happening, you can recognize that we are all consuming this, like insane amounts of media, and that has to have some kind of impact, and that really pushes you to start asking, well, what impact is that having?

Andy Luttrell:

And that’s more time than we spend with other human beings it sounds like, right? If the numbers shake out.

Sohad Murrar:

It is. Yes. Yes. Yes. I mean, it’s across different platforms, but it’s pretty jarring when you hear those statistics. You’re like, “What are you… How are people functioning?”

Andy Luttrell:

My impression too is that people in communication have been talking about media forever, right? They go, “Yeah, of course. You just discovered that media’s important?” But as a young social psychologist, how did media sort of enter your field of view as a viable thing to start testing from a psychological perspective?

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah, so it was actually… This is a funny story because when I was interviewing for grad school, I was at UW Madison and I was interviewing with Markus Brauer, who ended up becoming my PhD advisor, and he asked me if I had to develop… This was one of my interview questions the day of. He asked me if I had to develop a prejudice intervention, what would I do? And in the moment, I hadn’t thought about it extensively, but I had always thought about, well, the media creates this negative perception of Muslims and that’s something I can really relate to, and if it can create a negative perception and it creates a lot of prejudices, something can create it, ostensibly it should be able to also deconstruct it.

So, I threw that out there, and then afterwards I like… You know, you go, and you start researching, you’re reading, you’re like, “Did I give a good answer?” And then I started finding all of these interesting articles from communications, and a little bit in psych, but very little in psych, on how television and film has been used to affect all these different changes, and even in intergroup attitudes, and so I remember reading about The Cosby Show and the effect that The Cosby Show had on American audiences, and for me that was super interesting because I always thought of The Cosby Show as this kind of groundbreaking TV show that had this positive impact on people’s perceptions of African Americans, and here was research that was saying, “Oh, when we actually asked people about it, it turns out they end up subtyping this. Based off of the Cosbys, the Huxtable family is not representative of the American perception of who Black people are in the U.S.,” and so they become this exception to the rule, and then there’s other research that shows, “Oh, when you ask people about it, it turns out that they think that the Huxtables are able to do it, so other Black people can do it too, and racism is not an issue in the U.S.”

So, it kind of has this negative effect, this effect that we didn’t necessarily think of. Similarly, there’s the Archie Bunker effect, where All in the Family was created to kind of have this… to create kind of a farce out of how prejudiced Archie was, right? Like this is ridiculous, who holds these attitudes? But in light of the general social context in the U.S. broadly, people ended up really relating to Archie and liking his prejudices, and kind of agreeing, and becoming more polarized in their own prejudices as a result of watching. So, again, there’s this counter effect, but there is this recognition that this avenue, this kind of medium can really impact people’s attitudes and behaviors. It then starts to create this question of, “Well, how do we do that? How can we use this avenue?”

And I think that’s when it really became an empirical process for me. Well, it’s clearly having an impact. It’s kind of negative, counterproductive in some ways even when the intentions are positive, so what do we gotta do to have the positive effect? And so, that motivated my research.

Andy Luttrell:

Yeah. It seems like there’s a world where it feels like you go, “Well, yeah. Of course, media should matter.” In the same way that you think about all these other interventions, like the D.A.R.E. program, or other education interventions where you go like, “Oh, of course all we need to do is share this message, dismantle some assumptions,” but then when you actually go in and test whether those programs are doing what they’re supposed to be doing, you might find like, “Oh, this is having the opposite effect.”

Sohad Murrar:

Oops.

Andy Luttrell:

Drug use is increasing in schools or the D.A.R.E. program, which as a meta point is the importance of actually looking at these things. But the question here is like it’s not a simple question of can media reduce bias or reduce prejudice, but it’s more like how can it do that, right?

So, if media can stand as a way to create and disseminate stereotypes and prejudices, and also, even when trying to present a more representative view of the world on television, it may only reinforce those prejudices. What do we know about like, okay, what has to happen for these media outlets that take up so much of our daily attention to actually make some change?

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. So, I don’t think… We can’t take for granted, it has taken some time to even establish that media can have the positive effect, so I think that was really the first question, and that was something I started to tackle very early on in grad school and is something that I continue to do, is first establishing a link. Can we use it? Can we use TV? Can we use film to actually have this positive effect? And I think at this point we can say with some degree of confidence that from communications literature especially and more so now in psychology too, we can say, “Yeah, you can really use this avenue to create positive intergroup attitudes and reduce people’s prejudices.” And of course, then you’re asking yourself why. How? What do we gotta do?

And I think there are a few things that we have been exploring and I think we can definitely conclude like, “Okay, you want to do X, Y, and Z,” and I can get into those. But I think that this is kind of where we need to be questioning things at this point. And this is what my current research is focused on. So, it’s kind of a mix of things. On the one hand, on the psychological perspective, it’s what psychological processes do we need to activate in order to actually reduce people’s prejudices first, and then second, what content do we need to include in media to activate these processes? So, it’s kind of two pronged, and we need to kind of be figuring out both of these things.

And there are a few things that we already know. Some of my research has shown that we need to make sure that the characters that we’re representing are easy to identify with. So, you don’t want them to be so unique, or just so out there, that the average audience member can’t relate to them. They’re just so unrelatable, which is a little bit of maybe what you end up with when you have a super high-class family that doesn’t necessarily… Even the average American, who relates to a family with a lawyer mom and a… What was he? He was a doctor, right?

Andy Luttrell:

Doctor something, yeah. Doctor of something, at least.

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah, so not necessarily always the most relatable to the average American, so you want to kind of represent your characters in relatable ways so that the audience can identify easily with those characters. Creating fun and exciting narratives, making sure that they’re very immersive by nature is really important, and just interesting narratives. You want to represent the minority characters in your TV shows, in your films, in ways that are not too contra-stereotypical. You want to represent them in ways that are heterogeneous. We know kind of perceiving outgroups as homogeneous leads to prejudices. You know, you kind of see them all as one and the same. Representing their heterogeneity is really important for deconstructing the basis on which we build prejudices, so there are all kinds of different things that we have to start to consider to actually create media that leads to prejudice reduction rather than keeping things where they’re at, or even kind of having these boomerang effects.

Andy Luttrell:

Have you read, Kal Penn just came out with a biography, or a memoir or something. I don’t know if you… I just finished reading it like a week ago.

Sohad Murrar:

I haven’t had a chance to read it, but I’ve come across it. Yeah.

Andy Luttrell:

Yeah. It speaks to these things. You know, he tells all these stories as a young Indian American kid in Hollywood, going out for roles and just encountering either like, “We want you to be a very specific stereotype,” or, “There’s just nothing else we have for you.” To go out for some default role really means going out for a role for a white guy. And there was really… It was just so hard to break through. And trying to desperately, and he’s an example of someone who succeeded, but that is not sort of the typical story of landing roles that are true to the actual experience of an Indian American person, but that are not the stereotypical experience that the public has, right?

And so, you mentioned that we do have evidence that these media can chip away at bias. What does that evidence look like? Can you point to anything where we could say like, okay, here’s how we know that whatever it is and however they did it, some manner of media was able to change people’s assumptions about a group?

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. I can refer to my own research. I can refer to some other folks’ research, as well. But I think generally speaking… So, I’ll start with my own research. So, I’ve looked at the ways that TV shows can have a positive effect on people’s intergroup prejudices. Specifically, I’ve looked at this really popular TV show in Canada called Little Mosque on the Prairie and how that has been able to kind of… It was able to kind of reduce people’s prejudices towards Muslims broadly as a result of watching that show in comparison to a control condition that watched Friends. And in that study, a big underlying mechanism was identifying with those characters. Again, those characters were relatable. They were flawed. They were dealing with similar issues that anybody would be dealing with, so they were just kind of easy to imagine yourself becoming friends with, or identifying with in certain ways, feeling similar to them, relating to them, and that played this important role, and so people’s prejudices, both explicit and on the IAT, that implicit measure of prejudice that we have, was changed after watching the TV show. And we found those effects a few weeks later too, so they kind of had this lasting change which was really exciting.

And there is a growing body of research, especially from the communications literature, that shows that exposing people to TV shows or films to individuals or groups from marginalized backgrounds, or some kind of minority group, really does improve people’s attitudes towards those minority groups generally. So, I think that there’s a lot of promising evidence. I think in reference to what you’re saying, kind of what Kal Penn was talking about, and I think it’s something that I’ve observed too in my interactions with people from Hollywood is that a lot of times the stories are written and they’re based on stereotypes, and I think a part of what the issue there is that the stories are not being written by the characters or people that share backgrounds with those characters.

It’s kind of just ideas that people have. A lot of times they are based on stereotypes or what kind of news media is portraying of certain groups, or sometimes it’s completely just out of nowhere and they don’t necessarily know why they’re making certain writing choices. And that’s what ends up getting scripted, and accepted, and there’s kind of an inertia. There’s this point where creators are… They’re kind of just, “Okay, we’re in the middle of this, and the studio has accepted this, and now this is what we have to run.” And I’ve talked to people who’ve had realizations later, like, “Oh, oops. I just told people that this whole country in Africa is plagued with this issue of female genital mutilation and after doing research I found that… Oh, they’re not known, that never happens in this country. Now the whole world is gonna hear that this is what’s happening here.”

But you know, the show runners are running with this, and the studio, it’s really hard to go back on it at that point. And so, I think getting people into the creative process who actually have these backgrounds, who can check it really early on, or they’re the ones who are actually writing the stories, is very, very important. And I think we’re seeing more and more of that, which is exciting.

Andy Luttrell:

I’m a big animation fan and have been for a long time, and I feel like there was like a distressing era of cartoons set in exotic cultures, let’s say, that present a very white American perspective on what those stories might be. But this cool new wave now, where the process is very much in touch with giving… handing the reins to people to direct, and write, and draw, and paint the backgrounds of the places that they’re from, of where their families are from, and the experiences that they have, and that has struck me as a very potent way of doing this, right? Because in an animated film especially, every pixel of every frame is invented from nothing. It’s not like you can just go like, “Well, at the very least we shot the movie in Mexico City.” You’re like, “No, we had to create the most authentic version of this place and these people as possible from the ground up, and the only way you can really do that is to lean on people who kind of have it in them to tell that story.”

Sohad Murrar:

Absolutely. And I think we are definitely seeing much more of this, and again, in that Nielson report, it’s a very informative report, I was reading they had analyzed… It was over 1,500 programs in the U.S. and what they found was that I think it was some 70% of those programs now have representation of somebody from a marginalized background, but then interestingly there are surveys that ask people from minority groups, “What do you think of that representation? What does that representation look like to you?” And a lot of people say, “Well, it’s still stereotypical and it’s still not really representative.” But these are definite improvements because there are more and more creatives from different groups involved in the process of the creation, so I think we’ll continue to see that and you’ll see kind of more and more people creating shows or movies that represent at least in their perspective what is their group, or what their culture is like, and I think that all of these different new platforms that we have create more spaces for people and different ways of actually creating shows.

So, there are Netflix shows, or Hulu shows, or all kinds of different… Amazon Prime shows. Whereas before, it was kind of network television is what we have, and this is how you make… There are these big conglomerates of studios and you either get a contract with them or not. But now there are these streaming platforms and all kinds of ways that you can get your materials out there, and I think that has led to an increase of minority representation in the creative process, not just in representation, but in the process itself. And that is kind of creating this new era for us.

Andy Luttrell:

So, one of the things I’m curious about is you were talking about some of the studies that you had done comparing different TV shows to each other, and the framing struck me very much as you call it entertainment education, and there’s a little bit of an indication that these stories are not just stories, but they’re like in at least some part intentionally functioning as like a stereotype-busting exercise, right? Or like a way to deliberately say like, “Oh, you’re wrong about the way you think about certain groups. Here’s a better way to think about it.” Whereas the conversation we’re having now is about any story, right? And not about deliberately being educational, but just like increasing representation in a way that’s authentic.

And so, what I’m curious, there’s like a moral argument to say, “Well, yeah, we should just increase representation and tell authentic stories because obviously we should be doing that,” but to the practical point of what its effects are on a public, I’m just curious to get your take on do you think that it’s important that these narratives have an element that deliberately addresses myths and issues of diversity and identity? Or is it enough just to change the landscape of who is represented in our media?

Sohad Murrar:

I think that we need to do it deliberately. Because a lot of times, people are creating narratives based off of their intuitions, and in some cases we can, based off of what we know in psychology, sometimes you can read a script and you could say, “I really think this is gonna have a negative effect.” This person is so contra-stereotypical, I don’t think it’s gonna have the positive effect that you think it’s going to have. Or you’re taking on so many identities here, this message is coming through really, really explicitly, and if somebody’s a little on the wall about how they feel about this type of person, or somebody from this group, this is gonna be a little off putting for them. Or whatever it might be.

So, I think it needs to be deliberate and there is more and more on how we can use edutainment or entertainment education, which is essentially how we can create narratives in media, TV shows, soap operas, radio shows, whatever it might be. Kind of just depends on the country, too, how we’re framing it. How we can use these to portray very particular messages to people about positive intergroup relations, about intergroup conflicts and how to overcome them. It should be a deliberative process. I think we should be using the knowledge that we have from psychology and other disciplines to create messages, very deliberate messages that we’re communicating in these media, because I think when you look at and you talk to the creatives, it’s always very surprising to me.

I used to have this conception that it was a very deliberate process, that prejudice is very much so something that there’s this group of white hetero males sitting in a room somewhere saying, “Let’s create these negative attitudes.” Okay, it wasn’t entirely that, but you know, I thought it was a much more deliberative process, but upon actually interacting with people in Hollywood, I realize it’s really they care a lot about entertainment value, and sometimes people have good intentions but really they just want to increase entertainment value as much as possible and don’t always recognize the social collateral of that. So, helping people see that hey, there are consequences to not thinking about this, you should really think about this, or helping them see that I know you care about this and you’re thinking about affecting positive change, but the approach you’re taking isn’t necessarily what we would think would work based off of the prejudice literature. Not necessarily media literature, even.

So, I do think it should be a deliberative process and I think that’s the direction we’re moving in, and there’s a lot of receptivity to kind of incorporating more positive messages. I do think there’s always this kind of… there’s this point of conflict a little bit between the creatives and kind of the scholars or the academics who you come in and you speak very different languages, right? People do not want their creative process affected by anybody, like I have the freedom to do what I want creatively. Why am I gonna listen to you? So, you really have to kind of highlight the effects and the outcomes to people like that.

Andy Luttrell:

So, you’re talking about interfacing with Hollywood creative types. Is this… This is some sort of consulting work that you’ve done in the past? Or like what has been your experience in terms of being at that intersection of scholarship and the creative… the folks who are running the show?

Sohad Murrar:

It’s been an interesting process. It kind of started in grad school when some of my research got some media attention and then people started reaching out to me. But it has kind of evolved into… Yeah, just something that’s happening pretty consistently where people reach out and ask me, “Hey, what do you think of this script? Can you read this script for me?” And it’s just interesting because it’s people who care and they have ideas, and they’ve already incorporated them into scripts. Sometimes they’ve even run pilots and they want some feedback. They just want to know like, “Hey, what do you think of this?” And sometimes they actually go off, and I usually write an analysis for people, like, “Here’s what I think based on your script,” and sometimes they go off and they change what they wrote. And I find that impressive. I’m just like, “Good for you.” I’m happy that you’ve done this. It’s great.

But that’s generally what it looks like. But I will say the people who reach out are the people who care, and this is a deliberative part of their creative process and their production process. So, it’s not the case that everybody’s doing this, but there are more and more people who care, and I think a part of why people are caring more is of course there are some people who just care, and it’s great to think that we just have people who have these egalitarian values, and they just want to create a more positive world, but I think that there is some pressure to create more conscious media, and to make sure that you’re representing people, and make sure you’re representing them authentically, as you said, and not creating these negative outcomes.

So, there’s this new, or at least there’s this shift towards more and more realistic, and I do not want to say always positive, but just a more realistic representation of individuals from minority backgrounds in media.

Andy Luttrell:

So, for any budding screenwriters who are listening, is there any feedback that you find yourself giving on these scripts routinely? Are there themes where you go, “I’m constantly mentioning to people that this is not the way to do this.”

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. The one thing that always happens, there’s some degree of stereotyping that is happening, or counter stereotyping. There’s a lot of times where people create this counter stereotypical exemplar that might be really easy for people to process but is not going to be something that leads to that kind of change, because I really do think people subtype those really out of this world characters, and that’s a piece of feedback I’m almost always giving.

Andy Luttrell:

It got a little jargony there with counter stereotypic exemplars and subtyping, so what would be an example of what you mean and how it’s counterproductive?

Sohad Murrar:

So, without kind of mentioning the show, I’ll just give you an example. There was one time somebody approached me about, and this happens a lot, but it’s not necessarily just Muslim characters, but it does happen to be the case that I’m a scholar of intergroup relations and prejudice and also a visible Muslim, so people will approach me when they’re representing Muslim characters, and there was this one Muslim character that was being represented in this show. It was a woman from a Middle Eastern country who wore the hijab, who was also being represented as a lesbian. She was being represented also as like some kind of political disruptor and there were like three other things in there that just really made her very counter stereotypical.

Andy Luttrell:

Kind of like a forget everything you think you thought about Muslim women. This person is the opposite.

Sohad Murrar:

Yes. And that’s who… Yeah, exactly. And so, I think it becomes a little hard for somebody who doesn’t know a Muslim, somebody who’s never interacted with a Muslim before, to kind of deconstruct all of their stereotypes in one character. And it becomes too much, right? This is just unbelievable. This is clearly a fake representation. So, just pull it back a little bit. Maybe just choose one marginalized identity and emphasize that, because again, this is multiple identities. You’re kind of conflating all of the different struggles that this person is experiencing and individuals from these groups experience, and condense it into one character, and it waters down the different struggles that people encounter who have these identities.

So, maybe just pull back a little and just focus on one little thing and make the person relatable in all the other ways. But this is a totally unrelatable person for a vast majority of people, and if again, you’re kind of ambivalent, or maybe you’re even a little prejudiced, this is a bit much, right? If you’re super open and you’re like, “Yeah, everybody’s great,” this is fine. This character’s fine. But you’re not necessarily the people who need changing. The people who need changing might find this character a little difficult to relate to or process.

Andy Luttrell:

Is there any sense that working in the domain of fiction also sets up subtyping more, where people can more easily go, “This is too much and it’s not even a real person,” so like why would I even let this change how I feel about actual people in the world?

Sohad Murrar:

It could be the case. I definitely think that could be the case. But I also think that people make choices about the types of media that they’re consuming, so sometimes when you’re watching something fictional, you want something totally escapist and out of this world, because you need that, or you want that, and I think that’s a part of why media is so powerful, because you’re still affecting people’s perceptions of the world even if it is fiction. So, make it fictional in certain ways but not so fictional that it’s impossible to generalize to the life that you have, or you can’t kind of imagine interacting with those characters that you’re watching, and consuming, and becoming intimately engaged with through your consumption of that media.

Andy Luttrell:

Great. I was almost gonna ask in terms of advice for using these narratives, but I kind of think we’ve pretty well circled through this world of how the media do these things, and so I’ll pivot a little bit to other work that you’ve done that to me seems very similar in that it’s about the social norms that people experience or perceive around them as another way into changing minds about social groups. So, just to sort of set the stage for this, could you give us a sense of what do we mean by social norms as an idea and why they’re a potent influence on attitudes? Not just for prejudice, but just for attitudes in general.

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. I mean, generally speaking, social norms, I think of them as those unwritten rules that tell us how we should behave, what we should think in certain situations, what we should do in certain situations, so that we’re kind of behaving in a functional way for us, in an adaptive way for us. And it’s incredibly important. Social norms are so important. They keep society functioning in an orderly and cohesive fashion, so we need norms to really just kind of guide us and tell us, “Hey, here’s the appropriate behavior. This should generally get you by.” And behaving in a way that doesn’t fit this is maybe gonna create some turbulence or some issues for you and for those who are around you.

So, those are generally what social norms are, and I think people are motivated to kind of follow norms, whether they’re aware of it or not so that you fit in, so that you’re not kind of coming off as this person who doesn’t belong, or as kind of this foolish person who doesn’t know what to do in a certain situation. Yeah, so I think very important and highly influential on our attitudes and behaviors.

Andy Luttrell:

Where are people learning these norms? I mean, there’s many ways, but just to give a flavor of what they are, where they come from, how are people developing a sense of what is normative?

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. The social contexts that we find ourselves in, what are people doing around us? And I think in our current world, social media, the media in general, entertainment media, we see what people are doing, what people are liking, what people are kind of posting on their different media platforms, what characters are doing in TV shows, so there are all kinds of ways that norms are communicated. I mean, historically it was maybe through day-to-day life, but day-to-day life looks so different for us now given that we do spend so much time on media, I think that social norms are most powerfully now communicated through media.

Andy Luttrell:

And I think also what’s interesting is that these needn’t be real norms, right? They can be all in your head. You’ve given the example in some writing that I always think about too of drinking, underage drinking in college, and how by the actual numbers, it is not as normative as many college students believe, right? But it’s the belief about the norm that drives behavior. So, if I think most of my peers are out drinking every weekend, that feels to me like a motivator to engage in that behavior. But if I can break through and be like, “Actually, you know what everyone? The numbers are not what you think. It is not quite so popular to do this. Many fewer of your peers are doing this regularly than you think,” that can actually be a powerful way to cut down on that behavior as people go, “Oh, so this is not what everyone’s doing?” So, I just have less of a drive then to do this myself.

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah, so that’s HW Perkins and Alan Berkowitz’s work on drinking behaviors, and I think the numbers are like if you perceive other college students average drinking, like how many drinks they have in an outing is five drinks per outing, you’re more likely to drink five drinks per outing, and also even if that means… Even if at the same time people are only drinking on average two drinks, it doesn’t matter. If you perceive it to be five drinks, you’re more likely to drink five drinks. And that’s really based off of the social perception, so what you’re getting at is what we believe to be socially normative is what actually influences our attitudes and behaviors, and not necessarily what the actual norms are. Which makes sense, like why would something we don’t perceive affect us? So, yeah, we have to perceive something to be normative for it to actually have some impact on us.

Which I think is, again, why the media is so powerful and influential in this domain, is because it’s a really quick way, very easy way to bombard somebody with a message, whether it’s a conscious message or not, that this is normative. And I think that this is an approach that’s often used in the consumer domain and commercials where you want somebody to buy your product. You want somebody to consume whatever it is you’re selling them. You communicate to them that this is the normative thing to do. Most people are doing this. Most people want this… I don’t know, McDonald’s burger, because it’s the coolest thing in the world or whatever it is.

Andy Luttrell:

A billion hamburgers sold. I mean, McDonald’s is the example people give because under the sign it’ll say like… For years, it was a certain number of hamburgers that had been sold, and now it’s just like, “More than billions,” like it’s too big now, but you should know everyone eats these.

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. Exactly.

Andy Luttrell:

And so, I’m making this connection now, but I talked to Chris Bail for this podcast last year, and he does work on social media polarization and politics, and part of the insight there is to go… If you look at public opinion polling, huge numbers of people are moderate, slightly lean in one direction, or don’t even really endorse a particular political ideology. But the message we get from social media is prominent displays of extreme political opinion. And it sort of gets us to think like, “Oh, there’s a lot more political competition among everyday Americans than probably there actually is.” Right? If you actually go out and talk to a real person in the world, you’ll find it’s not nearly that contentious, which I think transitions us into work that you’ve done on using those perceived norms as a tool for understanding where are the other people in my environment landing on these issues, and how does that shape my own take on this?

So, what do we know based on all the work that you’ve done about how norms can increase social tolerance?

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah, so I think one of the things that we have to do before we get into this is always assess what the actual norms are. And what people perceive those norms to be. So, asking people when it comes to prejudices, when it comes to intergroup attitudes, where they stand, where they fall on the spectrum, right? Are you on the prejudiced side? Are you on the very open side? Are you somewhere in the middle? Are you ambivalent? Do you care? Do you not know what to do? Where do you fall and where do you think other people fall?

And so, when you do that, when you actually see where… When you ask people, at least when we’ve done it, we’ve asked people like, “Okay, what are your attitudes about diversity? What are your attitudes towards people from XYZ groups? How do you feel about people who are from groups that you don’t belong to?” We did it on a college campus. I mean, these are very liberal environments. They tend to be pretty open and by definition that’s a part of what you’re experiencing on college campuses is the diversity in thought, in people, in perspectives, ideologies, whatever it is.

But what we found on the college campus we were working at, which was UW Madison, is a vast, vast majority of people said that they’re open to diversity, and they value diversity, and they’re excited to be in a space where they can engage with people from different backgrounds, and they try to be inclusive of others. It was some 97% of people who said this. And of course, there were a few people who did not hold those attitudes and were prejudiced and didn’t care for diversity, but again, that is a minority of people. Most people are trying. Most people do care. That doesn’t necessarily say that they’re doing everything, necessarily mean that they’re doing everything correctly, or that they don’t behave in ways that are prejudiced, but they at least value it. They’re at least trying. Or they’re maybe sometimes a little fearful of doing the wrong thing but would prefer to be non-prejudiced.

So, I think kind of assessing those norms, getting the actual norms, figuring out where people are, and I think recent data show that more and more people are confronting prejudice. There was a recent Pew survey poll that showed that it was 64% that… I just remembered the number, of white and Black Americans, who have heard a family member or friend say or do something prejudice, confronted them. So, people are confronting prejudice more. Similarly with support for Black Lives Matter movement. Last year, after the killing of George Floyd, Pew did some research and MSNBC did some research together, and they found that more and more people are supportive of the Black Lives Matter movement, so there is kind of this inertia, there’s this change that we’re seeing towards a more open society. People are more positive. People are trying to be non-prejudiced. People are confronting prejudice.

So, that’s generally where we are with what the actual norm is. Of course, that’s not necessarily what the media represents, like you said, and I think that is because people kind of stay tuned into the polarized messages and especially the negative ones, right? We have this negativity bias. We really remember, we focus on, we have this fear that we have of whatever, for whatever reason, and we hone in on those negative messages because it becomes this kind of adaptive thing for us. We just need to make sure we’re okay or whatever it is, but we focus in on those negative messages, and we’ll tune into them much more than we will a completely moderate message.

Andy Luttrell:

Yeah. I want to have a news network of just moderate news stories. I’m sure I’ll make a lot of money. Lot of viewers.

Sohad Murrar:

Yes. Yes. Exactly.

Andy Luttrell:

And you know, it’s the kind of thing where… Yeah, like that gets attention, it stokes outrage, and so it sometimes feels like a useful strategy to be like, “Look at this crazy thing someone did or said,” but I think what you’d maybe argue is that doing that, going overboard by highlighting all of these instances of prejudice and bias, could be counterproductive by normalizing those behaviors. And if instead, our messaging was more about look at how most people support these movements, and most people are totally on board with making change, that might actually be the thing to move the needle.

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. I mean, social norms messaging and telling people, “Hey, most people are doing this,” or, “Most people are doing that.” That has been proven to be effective in so many different areas across domains. Getting people to go out and get their breast cancer screening, getting people to go out and get prostate cancer screenings, getting people to engage in more sustainable behaviors, to reduce their meat consumption, to literally, you had Bob Cialdini on, to reuse their towels in hotels. And it’s been wildly successful in creating pro-social changes, and so telling people this negative message, like most of us are biased. Most of us have… Especially I think it happens a lot with the messages about implicit bias, like everybody has implicit biases. This is the message we keep hearing over and over and over again, and I mean our research, where we kind of expose people to pro-diversity messages, most people are positive, most people are trying to behave in inclusive ways, most people embrace diversity, that’s what led to positive changes for people’s intergroup attitudes, led to more positive perceptions of the climate, and so on and so forth, so I would argue that yeah, we have to be really, really mindful of these negative normative messages we’re putting out there about intergroup relations, and diversity, and prejudice, because people tend to do what they perceive to be normative.

And in some of the research we’ve done, we actually looked at a video that represented minority students who were talking about their experiences with prejudice, and even though they weren’t explicitly saying like prejudice is really widespread, overall the message came through that here are 10 students talking about the discrimination they’ve faced on campus, as opposed to all of the times they didn’t experience discrimination, or all of the students who haven’t really experienced that. That video was not effective the way that the positive norm video was in creating that positive change, so I think it’s something we have to be mindful of. And it’s not to say that we should ignore the fact that prejudice and discrimination does exist. It does exist. But it’s not being propelled forth by a vast majority of people. It’s usually a small number of people who are behaving in these ways and again, have this kind of megaphone of media to share those experiences and share their negative and racist views, or prejudiced views, whatever kind of prejudice it might be.

But most people, you just don’t hear about. Most people, it’s fine. Like yeah, personally I’ve experienced Islamophobia many times in my life, but overall, day to day, it’s not everybody, and it’s not… Most of the time, I’m not experiencing it. Can I recall those experiences, those positive experiences as much as I can in the negative ones? No. Of course, I remember. I’m like, “This person did this thing.” But we really have to kind of remind ourselves of that and that most people are trying.

Andy Luttrell:

So, to get concrete about the messages, and if people are thinking about implementing similar kinds of messages, in the work that you did with UW students, what were the ways in which you were able to convey these norms in a way that you could see measurable improvements in all these outcomes that you were talking about?

Sohad Murrar:

Well, it should be no surprise that I used media formats to convey these norms. I used video and a poster, and the overall communication, the big message that came through in both of them was that UW Madison values diversity, embraces diversity, and people at UW Madison try to behave in inclusive ways. And the video is a short, five-minute thing. It was kind of these on-the-street interviews with students. We asked them what are your views on diversity, and so they’re talking about like I value diversity, I’m really excited to be in a place where I can interact with people who are different than me. We had some expert opinions, and so we had some professors and faculty who are doing research on this topic sharing what they’re doing, and what they’re finding. Again, this norm of most people care. That’s what surveys, thousands of people on our campus are saying, “We care. We’re trying. We’re open.” Very few people are saying, “Yeah, I’m not trying. No, I don’t like people from other groups, and I’m not interested.”

So, that was what was in the video. The poster, similar, it just had this kind of overall message we embrace diversity and value diversity. And then we supported it with some statistics on there, where it was like 95% of people or whatever it was agreed with the messages on this poster, and 83% were okay with putting their picture up, and so there was a group of students’ pictures on the poster itself. So, very quick, easy, subtle ways of communicating these messages, which I think is a part of what also leads to the impact that they can have and the effectiveness.

Andy Luttrell:

I watched the video right before we jumped on this call. Did you produce the video? This was made for the… I couldn’t tell, because it looked like something a university would put on their YouTube channel. I didn’t know if you had plucked something that the university had made versus you very deliberately designed this to do a certain thing.

Sohad Murrar:

No. Deliberately designed it, so I worked with somebody who was in the film department and he just kind of did the recording and editing for me, but the overall message, and the interviews and stuff, that was… Yeah, I went out and did this. Yeah.

Andy Luttrell:

Nice. The wrap up question I had is something that you discussed at the end of this paper, which is this approach works because the norm is tolerance, right? The reality is that these polling numbers support the point that you’re trying to make. But what about communities that are defined by a norm that is not this way, right? Are there ways that we can think about leveraging the same… one way to do it is dishonestly say, “Yeah, all your friends are super pro diversity,” even though we were just lying to this person. So, that’s one dubious way to go forward.

Sohad Murrar:

So, I don’t think that’s a good approach.

Andy Luttrell:

So, what is? Presumably, you spend some time thinking about this, or at least every time you present this, someone asks you this question of like, “What about the places where we might be the most concerned about making the change?” Because someone might argue like, “Oh, so if a place is already pro-diversity, that’s the place I can get people to even more strongly embrace diversity?” Is that where we should be spending the money? Don’t we want to change the harder to change? And so, what do we do there?

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah, so I think there are a few different considerations. One, you have to know who your audience is, and there are very different audiences, so there are obviously people on the two ends of the spectrum. There are those who are already where you want them. There are those who are really far off in the other direction and they’re gonna be the hardest to change, and then there’s the vast majority who fall in that middle ground, and kind of just don’t know. Just depending on what your goals are, I would usually argue those people in the middle, those are the people you want to work with. That’s where you’ll get the most bang for your buck and you’ll see kind of the most change. There’s some openness to change in the first place. Not to say that you can’t have an impact on those people on the other end of the spectrum there, whether they’re closed minded or whatever it is, but I think that focusing on that middle group is most worthwhile for the change.

Second, I do not think we should be lying about what the norms are. Again, I think people will just really have a lot of reactions to that. They’ll just kind of resist those types of messages that are total lies because that’s not what they’re seeing in their day-to-day life or that’s not what anybody around them is like. I think there are different approaches we could take to this. One of the growing strategies is to refer to dynamic norms, so shifting norms that, “Hey, there’s this wave of change that’s happening. Make sure you get on this bandwagon,” kind of a thing. And this is some of Gregg Sparkman’s work, where there’s… You kind of tell people, people are starting to do this. More and more people are behaving in this way. More and more people are non-prejudice. More and more people are trying to get to know people who are different than them. More and more people are behaving in inclusive ways.

There’s this thing that then happens where it’s like, “Oh, that’s where things are good. That’s the future, right there, and everybody’s gonna be acting in this way, so I better start behaving in line with that in anticipation of the future.” It’s kind of this pre-conformity, so anticipating the future I’m gonna do this. So, I would say focus on the shifting norms if it’s not already an established norm. And you can also decide that you want to kind of appeal to different categories of people and identity, so maybe within a very small community it’s not the norm, but you can always kind of refer to different communities, so if in my small town in the middle of the Midwest this is not the norm, but in the U.S., here’s what the data is showing. Most Americans are trying to do this. Most people are confronting prejudice. 64% is a norm that we could then take and present as, “Hey, this is 64% of Americans are confronting prejudice. There’s the shift that’s happening or here’s the norm that’s happening among us overall as Americans.”

So, that can be a different approach, so one would be kind of focusing on the dynamic norm. Two is identifying different types of categorizations of people that we can refer to and not just the most context-specific one. That’s if the norm is truly not in line with what you might want to produce.

Andy Luttrell:

Great. All right. Fingers crossed that we implement this, we see the changes, and yeah, this has been super interesting. And just want to say-

Sohad Murrar:

Actually, I just have one last comment.

Andy Luttrell:

Great.

Sohad Murrar:

And it’s not to say that this is the one approach, right? And obviously we want to also actually shift the social and institutional context that all of these types of individual level interventions are happening in, and we want to be implementing as many kind of evidence-based approaches we can for the individual level change, but at the same time we also want to kind of keep in mind that pushing for institutional change is really, really important, and systemic change is also really important, and kind of hand in hand we can see progress happening, and those norms can come through more clearly when institutions and leadership are communicating those messages through… whether it’s through laws, or policies, whatever it might be, or even just statements as leaders of organizations, or countries, or whatever it is. That’s another way we can be communicating norms is through those types of changes, as well.

Andy Luttrell:

Yeah. That is super important. And it’s a two-pronged thing, right? Changing the institutional stuff is like a direct effect on the problem, right?

Sohad Murrar:

Right. Exactly.

Andy Luttrell:

It’s a level at which change can happen, but it has this nice secondary effect of exactly what you’ve shown to be so powerful is communicating norms, right? Like if I… The moment I go, “Oh, same sex marriage is like now on the books, and that’s as a country what we’ve decided,” now that feels like, “Okay, I guess this is where we’re at now as a country.” That’s the norm and presumably that wouldn’t have happened if most people were vehemently opposed to it.

Sohad Murrar:

Exactly.

Andy Luttrell:

And so, yeah, this two pronger of like, “Okay, same sex marriage legalization is wonderful because it is same sex marriage legalization,” and then secondarily, communicating this norm that, and the hope being, is changing hearts and minds of the actual people on the ground.

Sohad Murrar:

Yeah. And I think they go hand in hand, too. They kind of affect each other. How are you gonna propel legislation forward if you’re not changing the hearts and minds of individuals, and so you kind of… You gotta do both. There’s value in all of it.

Andy Luttrell:

Very cool. Well, okay, now I’m saying thank you for taking the time to talk, and that was a very useful concluding note, so thanks again and we’ll look forward to seeing what’s coming down the pike next.

Sohad Murrar:

All right. Thanks so much, Andy.

Andy Luttrell:

Thanks.

Sohad Murrar:

Take care.

Andy Luttrell:

Yep.

Andy Luttrell:

Alright that’ll do it for another episode of Opinion Science. Big thanks to Sohad Murrar for taking the time to talk—it was great to catch up. I’ll leave a link to her website and the research we talked about in the shownotes.

And another shoutout goes to Susan Herbst—a political scientist at the University of Connecticut. She recently published the book A Troubled Birth: The 1930s and American Public Opinion. It’s a super cool look into when we even got the notion that there’s some sort of “public” out there for which we can know its opinion. It was in her chapter on radio that I learned about the program I talked about at the top of the show: Americans All—Immigrants All. And frankly, pretty much everything I shared is from that section of the book, so all research credit to Dr. Herbst on that. But I’ve been listening to the original radio show itself, and it’s been super fun in that quaint kind of like 1930s radio sort of way. You can hear almost all of the original 26 episodes on WNYC’s archives—I’ll link to it in the shownotes.

Speaking of audio entertainment, make sure you’re subscribed to Opinion Science wherever you get podcasts. I may not be able to play original orchestral music like in Americans All—Immigrants All, but I can promise a biweekly guide through the science of public opinion and communication. That’s gotta count for something, right? Check out OpinionSciencePodcast.com for all past episodes, including transcripts, and other fun stuff. Follow @OpinionSciPod on Facebook and Twitter.

Okay, that’s all for this time. See you in a couple weeks for more Opinion Science. Buh bye…